When equality feels like oppression

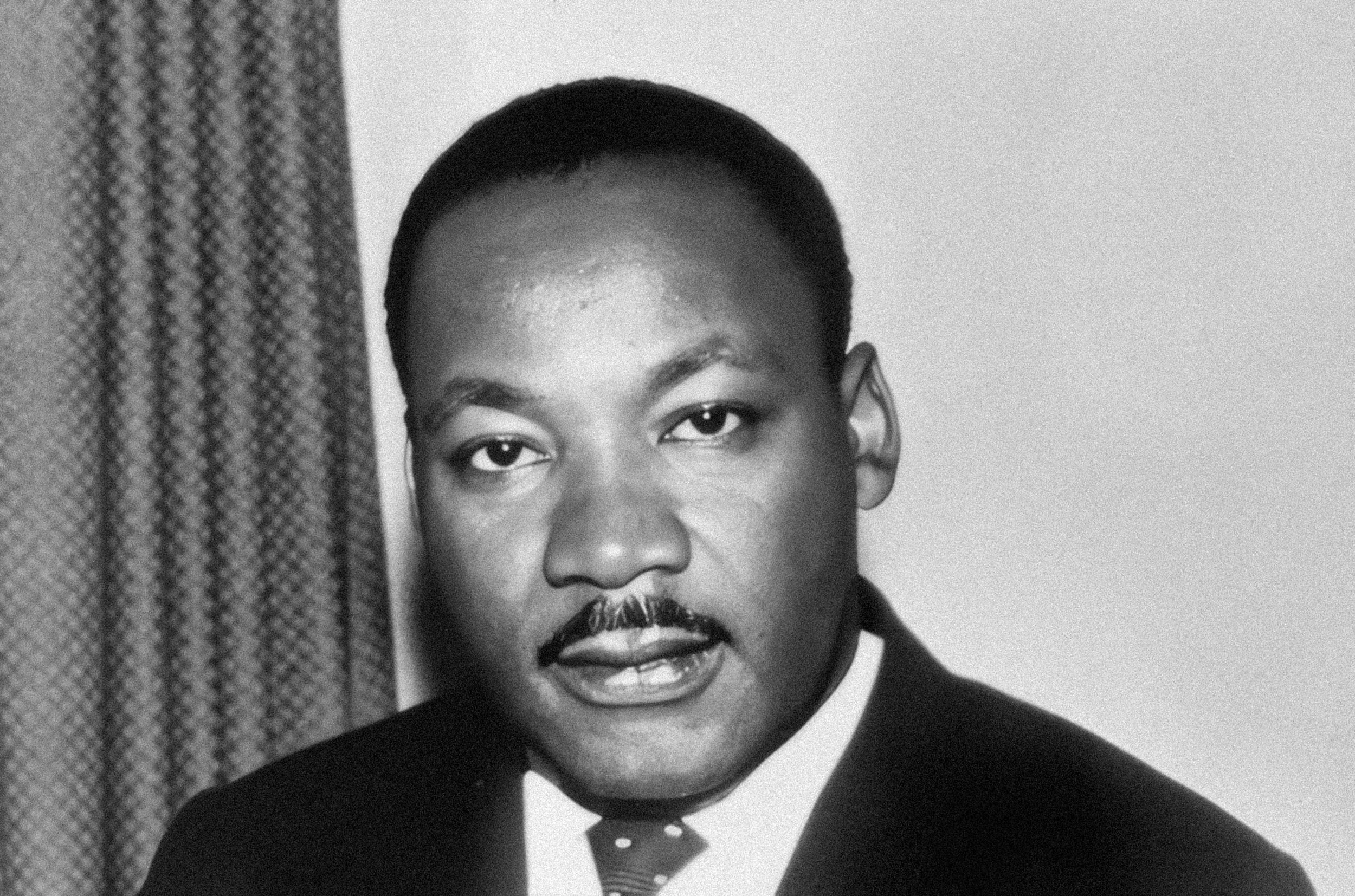

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Photograph by Florida Memory via Unsplash. State Library and Archives of Florida, General Collections Repository.

Dr. Marvin A. McMickle

In the summer of 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke these words in my hometown of Chicago, Illinois. “I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I have seen in Chicago.”

I was born in Chicago in 1948, and while I was well aware of the reality of racially based neighborhood segregation, the idea that racial violence and hatred was worse in Chicago than it was in Mississippi and Alabama seemed hard for me to believe. Many African American residents of Chicago had fled Alabama and Mississippi to escape racial violence. Emmett Till, a fellow Chicagoan, was brutally murdered in Mississippi in 1955. Everyone in Chicago was impacted by that brutal event — but it did not occur in Chicago. It occurred in Mississippi. That I could understand.

What I could not understand was that Dr. King said that racial hatred and mob violence was worse in Chicago in 1966 than it was in Money, Mississippi in 1955. There was a clear understanding about race relations in Chicago. Black and white people could work on the job side by side by day. We could cheer together on the weekends at Wrigley Field for our hometown hero, Ernie Banks of the Chicago Cubs. Everything seemed to work well by day so long as we retreated each evening to our own racial and ethnic neighborhoods. I attended an integrated high school located in a white community. Upon graduation, I worked at a print shop in downtown Chicago where I shared lunch with my white coworkers every day. It never bothered me that at the end of the day I went home to an all-Black community called Garfield Park. That was life in Chicago.

The play “A Raisin in the Sun,” written in 1959 by another Chicagoan named Lorraine Hansberry is about a family called the Youngers, who got a $10,000 insurance policy settlement after the death of the husband and father. With that money, they decided to move out of their crowded apartment on Chicago’s South Side and buy a home on the north side of the city in a fictional area called Clybourne Park.

There was great resistance to their plans, and the neighbors in Clybourne Park offered to pay the Youngers the purchase price of the house if that Black family would simply move somewhere else “around your own people.” The Youngers decided to reject that offer and move into the all-white neighborhood. By the end of the novel there was resistance and harassment, but there was no violence as would undoubtedly have occurred in Mississippi or Alabama. That was life in Chicago in 1966. I had heard that Chicago, along with Detroit and Milwaukee, were the most racially segregated cities in the United States in 1966. However, that simply meant that we lived in the same city — but not in the same neighborhoods.

Chicago never needed Jim Crow signs to enforce segregation; when equality threatened white comfort, flight and fury did the work just as effectively.

Then came 1966 and MLK’s bitter observation about Chicago. He spoke those words while driving away from a protest march in the Marquette Park neighborhood after being hit in the head with a rock thrown by someone protesting any attempt to have African Americans live in that community.

This was not Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, where police dogs and fire hoses were used to knock children to the ground. This was not Selma, Alabama in 1965 where African Americans were beaten by police officers while trying to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to demand their right to vote. This was my hometown of Chicago in 1966. Dr. King’s organization was called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, not the Northern Christian Leadership Conference. This was Chicago. But from King’s perspective, Chicago was worse than any city in the South.

I participated in the first marches that summer. Many of my friends at church rushed from the morning worship service, jumped on a bus, and were driven to the location where the struggle to integrate a white, residential neighborhood was about to begin. I was shocked and rightened by what I saw that Sunday afternoon in my hometown. I had seen a swastika on a flag in movies about World War II. Now I saw them in Chicago. I had seen the Nazi salute in those same movies. Now I was listening to citizens in my hometown, led by George Lincoln Rockwell of the American Nazi Party. Now I heard and saw all of this not more than five miles from where I lived in Chicago. Week after week and from one all-white neighborhood to another in Chicago the same thing occurred. “Niggers go home” as if we had just arrived from the African nation of Ghana rather than the Chicago community of Garfield Park just a few miles away. I remember marching down a street with tree limbs that overhung the street. As we marched along, a young white male was dangling from a tree limb shouting at us to go back to Africa.

Cars were burned. White police officers were spat upon, assaulted, and called “nigger lovers.” Many marchers were beaten. Death threats hung in the air. Mayor Richard J. Daley, who lived in an all-white neighborhood less than ten minutes from where I lived, did and said nothing to calm the situation. Apparently, he was as opposed to integration in Chicago as the white residents in Marquette Park, Gage Park, and Cicero. If you wonder how things worked out in Chicago in 1966, the city remained as racially segregated in its neighborhoods after Dr. King returned to Atlanta.

In 1970, just four years later, my own family left our Garfield Park home and moved to a new home in the Foster Park neighborhood. It was an all-white neighborhood in 1966. Then came the McMickles and other African American families, and within five years, Foster Park became another all-Black community in Chicago. When white people could not keep us from moving in, they moved out! “When you are accustomed to privilege, equality seems like oppression,” the saying goes. Those white people did not leave the job where they worked or their seat at Wrigley Field where they cheered for Ernie Banks. They just changed their home address so they would not live near African Americans.

Today, segregation in Chicago is just as bad. Chicago never needed Jim Crow signs to enforce segregation; when equality threatened white comfort, flight and fury did the work just as effectively.

Marvin McMickle is pastor emeritus at Antioch Baptist Church in Cleveland, Ohio, professor emeritus at Ashland Theological Seminary, OH, and retired president of Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School in Rochester, NY.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

Get early access to the newest stories from Christian Citizen writers, receive contextual stories which support Christian Citizen content from the world’s top publications and join a community sharing the latest in justice, mercy and faith.