The double exile of the Judsons from India

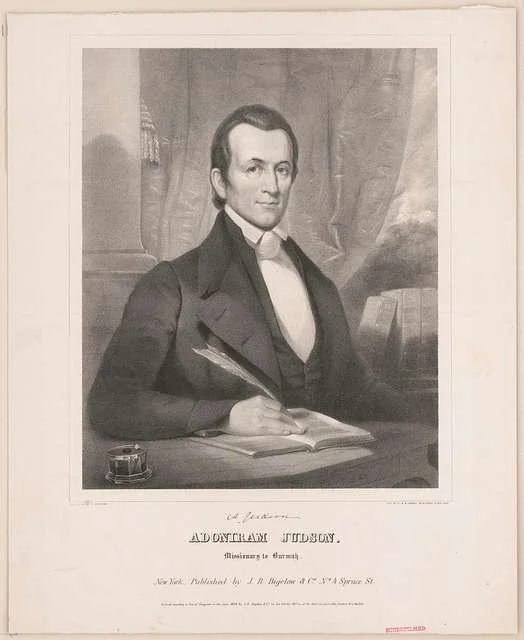

Adoniram Judson. Library of Congress, public domain.

Jerry B. Cain

Adoniram Judson, Jr., was commissioned as a missionary February 6, 1812, in a service setting aside five young men as the first appointed missionaries of the Congregational Church. Wives of three of them, including Ann Hasseltine Judson, came along, creating a team of eight adventurers. Ann and Adoniram Judson along with their friends Samuel and Harriet Newell departed Salem, Massachusetts, on February 19, 1812, aboard the Caravan. The other group of four, consisting of Luther Rice, Gordon Hall, Samuel Nott and his wife, Roxana Nott, sailed from Philadelphia on February 24 aboard the Harmony.

These eight young adults intended to rendezvous with British missionary William Carey near Calcutta (present-day Kolkata), India, for a short time of conversations and missionary training. At that time, the British East India Company (BEIC) exercised economic and political control over large parts of India. Missionaries were barred from British-controlled areas because of the fears that Christian proselytizing would antagonize local populations in India and disrupt trade.[i]

Soon after they arrived in India, Judson and Newell reported to a Calcutta police station explaining they would only be in India as long as it took to find a ship to Burma.[ii] The clerk explained they would not be allowed to remain in India but gave them a certificate affirming that they had reported to the police. Two weeks later they were abruptly summoned to the police station where they were told they were required to leave Calcutta at once and return to America on the Caravan even though that ship had no immediate plans to sail back to the United States.

These wannabe missionaries petitioned the Governor General of India, clarifying they had no intention to settle in Bengal and asked permission to stay only until their four friends on the Harmony arrived. On July 15 they were again summoned to police headquarters and were formally told they could not attempt a Christian mission in any British dominion or the territory of any British ally, including the territories in the East Indies (present-day Indonesia and surrounding island groups). Judson and Newell were then escorted back to their place of residence by a petty officer (a junior naval official) and told not to leave the residence without permission. The Newells soon found a ship, which, however, had room for only two passengers, going to Isle of France and left on August 1, leaving the Judsons alone in India. But soon thereafter, the Harmony arrived from Philadelphia and they were reunited with the other four missionaries. These six Americans made frequent but futile attempts to leave India by booking ships to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), Bombay (present-day Mumbai), and Isle of France (present-day Mauritius). When news arrived of the beginning of the War of 1812, they were suspected of being American spies for America and ordered to be transported to England, a prospect the young missionaries frantically tried to avoid.

Three of the group got away. “On November twentieth [Samuel] Nott, his wife [Roxana] and [Gordon] Hall went aboard the Commerce. So far as the authorities were concerned, they simply dropped out of sight. Furious government officials searched the city for them. But somehow the police overlooked the Commerce, perhaps not entirely by accident: then as today one department sometimes worked at cross-purposes with another,” writes historian Courtney Anderson.[iii]

Historical records offer a glimpse into the complicated nineteenth-century geopolitical realities behind Adoniram and Ann Judson’s path to missionary service in Burma.

The Newells were safely on their way to Isle of France. Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Nott and Gordon Hall were safely aboard the Commerce heading for Bombay. What could Luther Rice and the Judsons do to escape capture, expulsion, or incarceration? “It did not take them long to find out that a ship named La Belle Creole was leaving for Isle of France in two days. They had no particular desire to go there, but at least it was not England, and the [BEI] Company’s authority did not extend there…

“…Denied a pass [by BEIC authorities] they explained their problem to the captain of the Creole. Would he, they asked, take them on board without one? The captain, no more a lover of the authorities than many others in Calcutta, replied that he would be neutral. There was his ship. They might do as they pleased,” narrates Anderson.[iv]

It pleased the three itinerants indeed to board the Creole. The ship started down the Hooghly River toward the sea only to be stopped by a dispatch from Calcutta ordering the ship to anchor and wait because there were “passengers on board who had been ordered to England.”[v] For the next few days, the three missionaries and government officials played a cat-and-mouse game of being off the ship when the searchers appeared and hiding their baggage in adjacent craft when officials arrived.

After three days of hide-and-seek, the frustrated captain of the Creole dismissed the three missionaries from his craft and tried to resume his voyage. With their baggage bobbing in a skiff tied to a dock, the Judsons and Luther Rice sat in a tavern on the Hooghly River between Calcutta and the sea. Anderson writes, “And at this juncture, as they always believed, Providence took a hand. The meal was just being served when a letter was brought in. ‘We hastily opened it, and, to our great surprise and joy, in it was a pass from the magistrate for us to go on board the Creole, the vessel we had left. Who procured this pass for us, or in what way, we are still ignorant; we could only view the hand of God, and wonder… The next day we had a favorable wind, and before night reached Saugur… I never enjoyed a sweeter moment in my life, than when I was sure we were in sight of the Creole.’”[vi]

Thus, the Judsons made it to Isle of France where they found the recently widowed Samuel Newell. After much discussion, Luther Rice sailed for America hoping to rally Baptists in support of the Judsons, who had been baptized by immersion and thus could no longer accept financial support from the Congregationalists with integrity.

After much prayer and discussion, the Judsons felt a call toward Penang, Malaysia, and on May 7, 1813, embarked on the Countess of Harcourt, from Isle of France bound for Madras, India, where they arrived on June 4. “They were again under the jurisdiction of the East India Company from which they had lately escaped. Their case was immediately reported to the governor general, and no doubt existed that [his reply] would bring an order for their immediate transportation to England. No vessel for Penang was in the harbor. Their only means of escape was by a vessel bound to Rangoon. They therefore, on the 22d of June, embarked on board the Georgiana for that port,” writes biographer Francis Wayland.[vii]

The Judsons arrived in Rangoon on Thursday, July 13, 1813, and spent the rest of their lives as American Baptist missionaries in Burma. Their ministry would change the mind of the BEIC any about the role of religion, missionaries, and Christianity in their work of economic and political colonialism. In 1826 Judson would be released from a Burmese prison at the behest of the BEIC to create the treaties to end the First Anglo-Burmese War (March 5, 1824–February 24, 1826). This American Baptist missionary, though in exile, was the most qualified person in Burma to mediate between the British and Burmese courts, since he spoke English and Burmese fluently and understood both cultures. This unique position enabled him to play a key role in the negotiations that concluded the war. Finally, the undesirable became the necessary.

Jerry B. Cain spent his career in Christian higher education with 14 years as President of Judson University in Illinois preceded by 20 years as Chaplain and Collegiate Vice President at William Jewell College. He co-authored The History of the Karen People of Burma (2023, Judson Press) with Angeline Naw.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

[i] Until the Charter Act of 1813, the BEIC actively resisted missionary activity in its territories, often ordering the expulsion or “transportation” of foreigners who attempted to stay. In modern terms, these forced removals resembled what we now call deportation, but colonial authorities spoke instead of expulsion or transportation.

[ii] A day after the Judsons’ arrival on June 17, 1812, President Madison signed the congressional declaration of war against Britain, but the news would not reach India for weeks.

[iii] Courtney Anderson, To the Golden Shore: The Life of Adoniram Judson (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1956) p. 150.

[iv] Anderson, pp. 150-151.

[v] Anderson, p. 151.

[vi] Anderson, pp. 155-156.

[vii] Francis Wayland, Memoirs of Dr. Judson, Vol. 1 (Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1853), p. 118.

Get early access to the newest stories from Christian Citizen writers, receive contextual stories which support Christian Citizen content from the world’s top publications and join a community sharing the latest in justice, mercy and faith.