Navigating change: Lessons from ‘Downton Abbey’ on caring for church properties and people

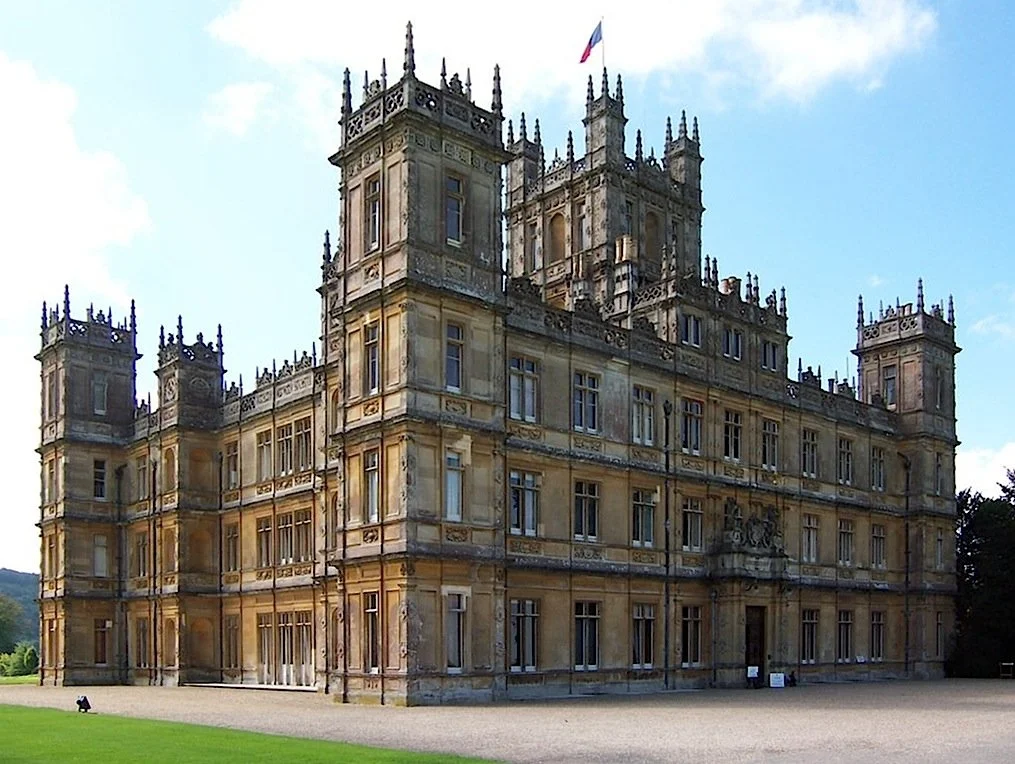

Highclere Castle. Photograph by JB+UK Planet via Wikimedia Commons. Used under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot

This fall the popular period drama “Downton Abbey” draws to a close with a third and final film, building upon the multi-season PBS series. Written by Lord Julian Fellowes, a member of the current-day British aristocracy, “Downton Abbey” traces the story of the Crawley family, heirs of a large estate in the early 20th-century rural Yorkshire countryside. The first season begins with the 1912 sinking of the Titanic, which sparks a crisis as the two heirs to the estate literally went down with the ship.

At the helm of the family and ancestral estate is Sir Robert Crawley, the Earl of Grantham. He is the last of his line, and through situations beyond his control, he finds his title and the estate’s future in question. While blessed with three daughters, Sir Robert is unable to pass this wealth to a female heir, by the laws of the era.

A distant male relative is declared the next in line. Matthew Crawley has lived his life with no thought of a hereditary title and its benefits…and burdens. Lord Grantham welcomes Matthew to visit the estate to begin preparing for the eventual assumption of his duties.

Walking around the grounds, the two men look at the large manor home looming in the distance. Cousin Matthew is not quite ready to consider this land and its wealth as “his” someday. Sir Robert observes,

Lord Grantham: You do not love the place yet.

Matthew Crawley: Well, obviously, it’s…

Lord Grantham: No, you don’t love it. You see a million bricks that may crumble, a thousand gutters and pipes that may block and leak, and stone that will crack in the frost.

Matthew Crawley: But you don’t?

Lord Grantham: I see my life’s work.

Sometimes we lose sight in congregations about our basic mission. We build places of worship and then spend more time worrying about upkeep than we do mission. When “Downton Abbey” first aired, I quoted Lord Grantham’s line about “a million bricks that may crumble, a thousand gutters and pipes, stone cracking in the frost” at church trustee meetings.

I felt some kinship between this fictional family and the real-life tensions of some Baptist trustees dealing with the blessing and burden of a large church property. We talked of the need to keep up with brick pointing. We knew all too well the damage from snow and ice buildup on slate roofing. We knew we gasped when opening the utility bill each month, knowing an endowment helped somewhat, but we would be just as happy if the building had downsized itself physically alongside the dwindling attendance. A building like this resembles Downton Abbey, a building and a generational inheritance at odds with the long-term sustainability of our church family.

Even as I quoted the bittersweet words of multiple building challenges, I also quoted the other part of Lord Grantham’s lines regarding the property: “I see my life’s work.”

Church buildings are part of who we are as Christians. We can make the case that the church is more about people, yet we need brick and mortar in some fashion to carry out some of our ministry and mission. We can express our faith and nurture disciples in virtual gatherings, yet it is also great to be in a physical space where we can break bread, offer the ordinances of baptism and communion and find some respite together as a “third space” that is not home- or work -related.

The fictional “Downton Abbey” mirrors the real-life tensions of some Baptist trustees dealing with the blessing and burden of a large church property. Do we see our “life’s work” in the brick to be fixed or the life of faith to be lived?

Getting congregants to seek more sustainable solutions for their sacred space needs is part of my vocational calling. A large historic building can keep its place in the life of a congregation, though we must be honest that it should not consume more than half of our resources simply to exist and be available for the limited gatherings of most congregations. I lament when a church spends so much of its already limited energy on brick-and-mortar burdens that they forget the need to transform the flesh and blood people of their community (or even themselves) through ministry and mission.

The “Downton Abbey” TV series and subsequent film trilogy show the long-term consequences of choosing how we live. While we marvel at the costuming and social graces of another era, we also see a bit of ourselves in what passed for high society with the often-unrecognized social inequity that it depended upon and benefited from.

The Crawleys live in the Abbey, desperate to keep up their standard of living. Downstairs, the many household and grounds staff get caught up in the changes sweeping society (the suffrage movement, World War I, and eventually the global economic crash of the late 1920s). Further, this life spent in “service” that they have known (and sometimes aspired to ascend within) become less attractive as such jobs disappear and greater opportunities await in urban areas far away.

In the final film “Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale,” the Crawleys have made it to 1930. Lord Grantham’s eldest daughter Mary married Matthew and bore a male heir, yet it is Mary who winds up entering the new decade as the functional decision maker for the estate as Matthew died in a car accident and their son George would need several years before he could assume any duties for his grandfather Sir Robert.

Lord Grantham himself struggles the most with the changes that keep on coming. He is at his best when playing the patrician role, yet when it comes to diversifying his finances, rethinking his business plan, or simply knowing when to step aside when the younger generation has a good solution, he falters. Even at this late date in the storyline, Sir Robert feels like a petulant child when faced with a decision he simply does not wish to consider.

In counterpoint, Lady Mary Crawley makes a modest shift in her understanding of the world. She can be vain and insular, yet she realizes when she must make the brave step forward and be assertive for the sake of the estate, rather than herself. She lives in a time and culture that is still quite far from the comparatively more egalitarian modern day, yet she is proving her mettle as she manages the various roles expected of a landowner with tenants and the well-being of the local village.

Looking back at the longer narrative now completed by the final film’s arrival, I can foresee “Downton Abbey” as a good binge watch for clergy and other church leaders. Do we see our “life’s work” in the brick to be fixed or the life of faith to be lived? Making that determination at strategic times will lead us toward our better angels and not keep us moored too cautiously to the buildings that have too often defined us and consumed our resources. That might help us think of other ways to serve the Lord!

Rev. Jerrod H. Hugenot is executive minister, American Baptist Churches of New York State.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

Get early access to the newest stories from Christian Citizen writers, receive contextual stories which support Christian Citizen content from the world’s top publications and join a community sharing the latest in justice, mercy and faith.