Challenging sanitized history: An interview with Imam Tariq El-Amin

Image courtesy of Imam Tariq El-Amin

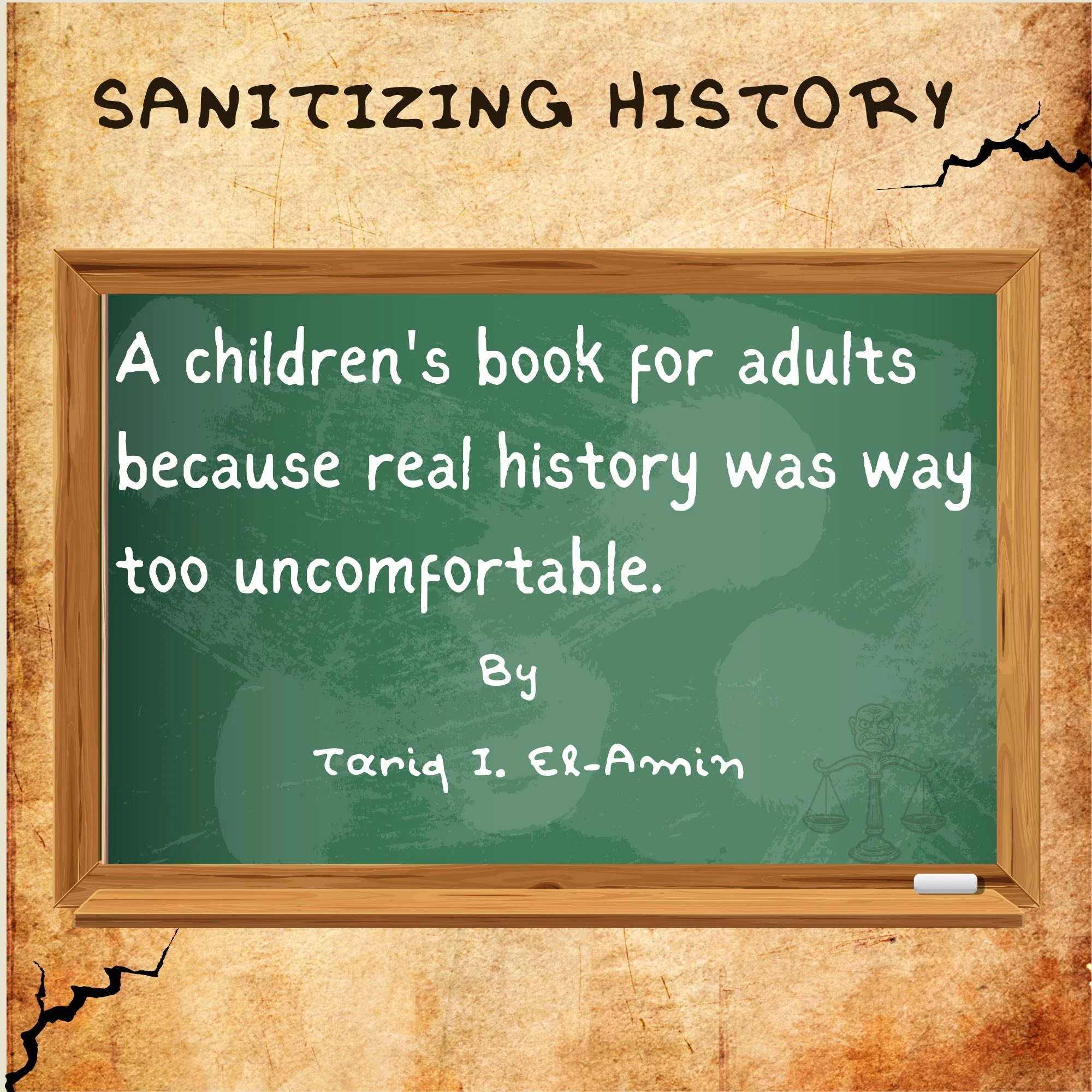

Rev. Dr. Anna Piela

The Christian Citizen recently interviewed Imam Tariq El-Amin, whose book, “Sanitizing history: A children’s book for adults, because real history was way too uncomfortable,” was published on October 22. His Facebook vignette project, “Sanitizing history,” released in the run-up to the book premiere, presented several white people of the past who were good neighbors, parents, and community members — but they also upheld white supremacy and cruelly treated African Americans, Native Americans, and immigrants. Yet this second part is usually concealed in history books and public discourse. El-Amin’s book addresses this silence and its repercussions today.

Imam El-Amin, I was really intrigued by the “Sanitizing History” series on your Facebook feed. How did this idea come about? And why is now a good time to release it?

What is the old saying? “If not now, when?” The urgency is always there. What brought the project about was a culmination of a few things. First, I saw how the educational system has been attacked quite aggressively in terms of what certain people feel is worthy of being taught. History keeps finding its way into our present, even if some folks want to give it a different coloring. So I want to share a different view of what has taken place in our nation's history around not just the enslavement of African folks, but the treatment of the indigenous Americans, the Chinese immigrants, Latino immigrants, immigrants from other parts of the world...and you can just go down the list of many atrocities committed against these groups to realize the horrendous exploitation that has taken place. And now all that is being presented in a much gentler and kinder tone.

Christians in particular, as People of the Book living in a majority Christian country, can and should take the lead on these conversations, inviting other Christians and people in general to interrogate reality.

So, the idea for the series was this: if you’re trying to whitewash or sanitize history, then I’ll play along with you to some degree because it’s ridiculous. And as you read these entries, you can see how despite the brutality, the ugliness of history, these people — the perpetrators — have also been revered. Today people don’t focus on the atrocities of the past. They don’t focus on the past’s ugliness and cruelty. They focus on the fact that this is somebody from whom people may have bought a great pumpkin pie at the bake sale. Somebody who ran a good business, they were a good neighbor...they overlook the things that were not just expressions of individual cruelty but were systemically and structurally supported and encouraged.

Would you say that this project is like a mirror for white Americans to look at themselves? Because you can be a great daughter or father, or neighbor, and at the same time, benefit from and uphold white supremacy.

Absolutely, very well put. In a nutshell, that is what it is. It’s an invitation for people to interrogate their positions and their own sense of value, where they might feel attacked personally. If they have judged themselves to be a good, charitable, compassionate person, does their compassion and their charity only extend to people who look like them? This is especially important with the rise of white Christian nationalism, which leaves out anybody who does not happen to have palm-colored skin. And that goes against the very teachings of which most folks should remember when they think of Christ — somebody who embodied love, sacrifice, and inclusivity, while also standing firmly for justice. So it is definitely an invitation for people to interrogate themselves and to interrogate their opinions and positions that they have. They really should ask themselves: how did we get to this place? What are the things that we’ve just taken for granted? They should look at these [sanitized] narratives and see how they shape how we see the world and ourselves.

The vignettes in the Sanitizing History project really show the genealogy of racism and settler colonialism. They show that racism is not just what we have today. It’s not just what existed in the '60s, but all this started when European colonizers came to this country. This project shows us the continuity of prejudice and systemic inequality. It was there right from the start. It was not about the Founding Fathers and freedom for everybody. It was freedom for the chosen few. Some of the people in the vignettes are historical figures. Are they all or are some of them symbolic?

They are symbolic. The goal was to use fictitious people that represented the real sentiment and systemic and structural realities of those times. This is a part of the social consciousness of that time. So it’s done with intention, because we can often deal with fiction just like a comedian can tell a joke — and they can tell the truth within the joke — which is received with less resistance, because it’s not named as a plain statement.

As I read them, I found they were very convincing. There was a variety of characters: there were men, women, and children, all with different backstories. How did you conceptualize these people who do seem like they're real?

The very first book that I read seriously — I was eight or nine years old when I read it — was a three-volume set titled “Ebony Pictorial History of Black America.” It was a history of Africans and African Americans, from the Middle Passage and slavery to the Civil Rights Movement. That was my beginning, my doorway into this particular realm of history. While all the figures in the project are fictitious, they are based on many amalgamated real stories. Even today, there’s a lot of commentary that is very similar in spirit, if not in words, to some of these entries.

White women are featured in the series quite prominently. White children are also mentioned. It is an interesting shift from the more typical depiction of white supremacy as tied to white men’s actions.

A great question. I think depicting supremacy as a result of white men’s actions is convenient and reductive. When we talk about patriarchy, with men having been in positions of power, we need to remember that it is not natural; people are socialized into it. There is this period of nurturing, which is not possible without women. So the project suggests that it is not just men who were awful on their own; these men went home to their families. They went home to women who benefited from the racist systems and structures designed to exploit and denigrate others. Women also upheld those systems. They were participants in them and helped to reproduce them. I thought that it would be inaccurate if I presented white supremacy and exploitation as an exclusively male domain.

I think it’s really important to show women’s role in white supremacy. When you introduced the series, you mentioned that there would be a second part called “The Ugly Truth.” What is that going to be?

Well, “The Ugly Truth” will be precisely what it says on the tin. There’s a sort of satirical version in “Sanitizing Truth,” where the person is shown in their “fullness,” with the ugly truth — their cruelty and destructive behavior — presented as ancillary, as a sort of background. Coming after “Sanitizing Truth,” “The Ugly Truth” will present the exact reality of the day. If we’re talking about the entry before the last about the slave catcher, he’s presented as an entrepreneur in “Sanitizing Truth.” He’s presented as somebody who was a stalwart of freedom from taxation, and an outstanding individual.

We’ve all been given a narrative about the past which has shaped our perception and engagement with the present, which ultimately impacts our future.

The ugly truth of it is that those who were following the natural human inclination towards freedom were deprived of it. They were brought back after they had escaped, and they were cruelly punished. What were the consequences for those who were caught and returned? There were many cases where free black persons on American soil were captured and brought into slavery in slave-holding states. It also shows how law enforcement today is the product of these slave patrols. “The Ugly Truth” is a bit more direct. It’s not blunted.

What are you hoping to achieve through releasing this series? Do you think Christians can do anything to support it?

Yes, absolutely. I think that the more we are critical of our positions, the more do we interrogate them. This is one way we can actually contribute to constructing a society that is really equitable. So much of the poverty and the misery that we see today is the result of intentional manufacturing of dysfunction. I think Christians in particular, as People of the Book living in a majority Christian country, can and should take the lead on these conversations, inviting other Christians and just folks in general to interrogate reality. Seeing how the representation of the past that we have been given is so often skewed, we may realize that we’re also living with a skewed view of the reality we have. For example, politicians and the media are telling us that there’s no inflation; that prices are going down — but you go to a store every day, and you see prices are not going down. Reality is not meshing with what we are being told, and we have to take responsibility for thinking for ourselves. So, yes, absolutely Christians can support this project. And if this series is a means of starting conversations, then I will consider that to be an absolute success.

What are the reactions to the project on social media? Were there any non-Muslims who engaged with it?

Yes, as a matter of fact. I know they’re not Muslim because of their language. One person said, “I’m absolutely here for your ministry.” They see it in that light: as a ministry. Others have responded with great appreciation. There are some people — they are probably immigrants who may not know our history — who aren’t really aware that this is a satirical series. And so I had to explain that we’re not celebrating these people presented in the vignettes. But by and large, the multitude have responded with appreciation for it and recognize it as an articulation of not only the past — the efforts to rewrite history — but also connecting that to where we are right now and how a similar effort is being made to shape our thinking about the present.

That’s great. I was wondering how your identity as a Muslim faith leader may have shaped this series. Did it play a role?

I think my Muslimness is always going to be there. It’s always going to have an impact. And one of the things that always comes to my mind is: you believe that standing firmly for justice is an act of witness to God. I think we should take any opportunity that we have, that I have personally, to speak the truth, to guide people towards truth, to help to establish justice. I just so happen to — none of us have any control over what bodies we come in and with what ethnicity and skin color — come through the African experience, African American experience here, so I’m more sensitized. I think because I’m sensitized, I have the responsibility to do this. So there is definitely a connection between my faith and my social justice work.

Could the series teach Christians of all sorts of backgrounds that Islam has been on this continent for as long as Christianity? A considerable percentage of the enslaved people brought here were Muslim. So it’s not like Islam is this foreign religion that the media so often implies. It’s time to acknowledge it as a fully American religion that might not be as big here as Christianity in terms of numbers but played a huge role in shaping the history of the United States.

Yes! I would also add to that, because as Muslims, we see this as a mission articulated throughout the Qur’an to engage with the believers, the People of the Book: Christians, Jews, Sabians...The Qur’an talks about the similarities between us. I think what’s important for us to consider is that our faith in God and our belief in the inherent dignity that we all possess as human beings is something that is deserving of our collective stewardship and protection. I think that, if that can come to the fore, where that becomes the central focus, this is so much bigger than polemics or proselytizing. This belief speaks to the dignity of the human condition. So if Muslims and Christians and Jews and Buddhists and Hindus and all of us, if we can agree to uphold that, then I think we give ourselves a chance for a brighter and just future.

Thank you. Are there any plans to ensure that the artwork that you created is going to be preserved? Because on social media things are fleeting.

Yeah, so you’re the first to hear this: this is a multi-layered project. There will be a website and educational resources as well. You could look at it as a game, a card game. And there’s also a forthcoming podcast that will be based on the series.

Is there a question that I didn’t ask and you would like to answer? Is there something that you would like to add to this rich conversation?

Yes. One or two people have responded to the series in a dismissive way. I’m hoping that we can somehow overcome that reaction when we hear something that we don’t like. On social media, if people want to just dismiss what you say, they don’t simply ignore it. They laugh at it, right? They’re not going to really think about it. If you find something unsettling, then ask yourself, why is it so? Maybe that reflection will allow you to engage with it in a way. You know, we’re asking people to really consider what has been given to us. We’ve all been given a narrative about the past which has shaped our perception and engagement with the present, which ultimately impacts our future.

Thank you for this conversation.

Imam Tariq El-Amin is a Chicago-based imam and community leader, serving as the resident imam of Masjid Al-Taqwa since 2013. He is a graduate of the Sister Clara Muhammad School system and holds a Master of Divinity in Islamic Chaplaincy from Bayan Islamic Graduate School. His work includes community service through organizations like The Abolition Institute and Arise Chicago, and he has hosted the live talk program Radio Islam.

More examples of the Sanitizing History vignettes can be viewed here, here, here, and here.

Rev. Dr. Anna Piela is senior writer at American Baptist Home Mission Societies and assistant editor of The Christian Citizen.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

Get early access to the newest stories from Christian Citizen writers, receive contextual stories which support Christian Citizen content from the world’s top publications and join a community sharing the latest in justice, mercy and faith.