Baptist theology, Islam, and ‘holy envy’

Rev. Dr. Anna Piela and Rev. Dr. Michael Woolf

“Holy envy” is a concept first developed by Krister Stendahl, a Lutheran bishop in Sweden and dean of Harvard Divinity School (1968–1979). He proposed three rules for interfaith understanding: “Let the other define herself (‘Don’t think you know the other without listening’); compare equal to equal (not my positive qualities to the negative ones of the other); and find beauty in the other so as to develop ‘holy envy.’”

By “holy envy,” Stendahl meant a curiosity and, indeed, desire to see reflected in one’s own tradition the strength and beauty of another. For instance, Christians might admire the Muslim conception of prayer and dedication to it or find beauty and meaning in the way the Qur’ān speaks about Mary, Jesus, or any number of the figures our traditions share in sacred texts.

Later, Barbara Brown Taylor would further develop the idea of “holy envy.” She was drawn to the “religious strangers who played lead roles in Jesus’ life,” such as the “Canaanite woman who expanded his sense of agency, the Samaritan leper who showed him what true gratitude looked like, [and] the Roman centurion in whom he saw more faith than he had ever seen in one of his own tribe.” In doing so, she finds that developing holy envy does not make one disloyal to one’s own tradition, but instead energizes one’s faith, making it more fluid, open to examination, and enlivened by the faith of others.

As my wife Rev. Dr. Anna Piela and I have journeyed with my Muslim friends, we have been drawn to their understanding of religion as an all-encompassing way of life, with sacred texts that offer guidance on everything from the smallest concerns to the great questions that humans have been asking since the dawn of our existence. When we speak with one another, we discover paths not taken by our own tradition, questions that are left unasked, and answers that we have been seeking. Of course, we see the similarities, but it is the differences that have most enlivened our spiritual lives.

After one conversation with a Muslim colleague at Challenging Islamophobia Together Chicagoland, an interfaith action network Anna and I have founded, we reflected for weeks on his statement that “Christians are always looking for the response from God, but in our tradition, we pray and God hears, but we aren’t always looking for God to speak.” What would it be like to think of prayer in this way? What changes might it bring to our prayer lives?

To be sure, as inheritors of a specific form of Protestantism, we lack much of the structured prayer life of our Muslim friends, and this often leaves us listening for God to speak, sometimes with frustration, sometimes with hope. We have developed a sense of awe in offering prayers, confident that they are heard, without waiting for a sudden epiphany. In short, our prayer lives are better for it. We offer this as a glimpse into some of the ways we have developed “holy envy” in our encounters. For each person, the experience will be different.

If we are open to practices of other traditions, then we will be challenged to reflect on our own. We are made stronger Christians through this engagement.

The key is that if we are open to practices of other traditions, then we will be challenged to reflect on our own. We are made stronger Christians through this engagement. The challenge is how to move such idiosyncratic experiences toward a more robust theology of interfaith engagement from the Baptist perspective. It is all well and good to engage in interfaith work because it produces positive effects in the world or in one’s devotional life, but theology provides a deeper understanding of why interfaith work can be so efficacious. To that end, we offer three theological starting points for developing “holy envy” from a Baptist perspective.

First, Baptist theology offers one of the most robust articulations of the priesthood of all believers in Protestant Christianity. As heirs to the Radical Reformation, Baptists took Luther’s original idea and applied it in transformative ways, always affirming that all believers have direct access to God. While the original idea is obviously explicitly Christian, the underlying principle behind the priesthood of all believers is incredibly useful for interfaith engagement: everyone has access to God.

While Baptists have typically understood this as a damning critique of clericalism and the tendency to vest authority and communication with God in the priestly class, it also contains a generative and liberating principle. Namely, if everyone can have access to revelation, then “believers” might also include adherents of religions other than Christianity.

Opening up the meaning of “believers” makes the church less central — and God more so. While it is important for the church to maintain its presence and for Christians to preserve their distinct practices and beliefs, that does not mean that we are to remain closed off to what we can learn from and do with members of other faiths. Just as Roger Williams warned those who would convert others by the sword that they should not play God, we ought not to play God by claiming that Christians are the only people God is speaking to, and if God is talking, then we ought to be listening.

Second, while Baptists have long recognized that uniformity of belief is not necessary for the functioning of the state or even churches, a theology of “holy envy” goes further, moving towards the celebration of diversity as something beautiful and integral to God’s design. A commitment to diversity is there from the beginning of Scripture, where human beings are the only creation that is said to have been made in the image of God, an image expressed in extraordinary diversity across cultures and places. God takes further steps to ensure human diversity, giving us different languages and customs in the story of the Tower of Babel. It is striking that so many Christians affirm God’s vision of diversity as being central to creation yet stop short of celebrating the immense diversity of belief that is present on a global scale.

The preeminent scholar of religion Mircea Eliade was right when he called us homo religiosus; we are made for religion. Yet, uniformity has never been part of our story. We seek meaning and arrive at different conclusions. For nearly the entirety of the Christian story, this difference has been perceived as threatening, but it need not be so. Certainly, it is threatening to a narrow understanding of the Christian story, but the sheer multiplicity of religious beliefs ought to make us pause and consider whether God also delights in the many different conceptions and understandings of the holy.

Christians actually become more capable interpreters of theological doctrine through interfaith engagement. They are better able to discern theologies within their own and other traditions that render God unintelligible or monstrous.

Indeed, because Baptists have historically thought of themselves as a “pure” church through believers’ baptism, they have always necessarily thought of themselves as a small, remnant people who have been called out from the world into a life of faith. Simply put, there was an acknowledgment from the beginning that church, the way the Baptists did it, was not for everyone. That necessarily meant that most people were not and would never be Baptist. It is not that God made such a great number of people to be damned, but that God made such an exuberance of different forms of worship and belief, and this ought to be celebrated. Because Baptists have never thought that every person will or ought to be Baptist, we should have an easier time accepting and honoring the diversity of God’s creation.

Building on the previous two Baptist distinctives, the principle of soul liberty offers another way of developing holy envy. This idea, so central to Baptist thought, most explicitly honors the diversity of thought and the human ability to reach individual conclusions about God. In recognizing the sheer variety of ways that God has revealed Godself to human beings, Baptists have welcomed diversity within their congregations and denominational life.

Simply put, this recognition of the sheer multiplicity of God’s intentions and directions not only makes valuing diversity possible, it makes it necessary to be a Baptist. It takes only one step further to apply this principle to other religions, welcoming God’s voice as spoken throughout the ages. In a world with so many ways of conceiving of God, might it not be possible that the soul liberty at the heart of the Baptist tradition requires us to honor the competency of those souls in knowing about God?

Taken together, these Baptist distinctives form a strong basis for engaging in interfaith work and developing “holy envy” through the theological commitments of the Baptist tradition. The building blocks are all there, present throughout the tradition. It takes only the willingness to apply them to our multireligious landscape to open the door to “holy envy,” to seeing God’s revelation in the faith of others. Doubtlessly, there will be some objections to this approach. Some may worry that “holy envy” would result in a devaluation of God’s revelation as we have found it in the Christian tradition, but this need not be so. When you look at the early church, you do not see an exclusive “religion” as we have come to understand it. Many early followers of “the Way,” as they called themselves, existed within Jewish communities, and some who were baptized by John sought fellowship with early Christian groups. It is only later that the boundaries became rigid, perhaps best embodied by the fourth-century theologian John Chrysostom who wrote “Against the Judaizers.” Chrysostom was writing against Christians who also celebrated Shabbat and argued that there needed to be a strict separation between Christian and Jewish communities

Furthermore, it has been my argument throughout this book that being in dialogue and partnership with other traditions, and developing “holy envy,” does not lead to an impoverishment of Christian theology. Rather, it makes that engagement sharper, more nuanced, and, frankly, more interesting. Consider the Trinity as a concept. In our experience, most Christian clergy, when asked to render an interpretation of the doctrine, eventually argue that it is a “mystery” of some kind that must be accepted on faith. Engagement with the rich critiques of the Trinity from Muslim sources does not typically shake people’s faith in the doctrine, but it does push them to elaborate on and further understand the relationship between the three “persons” it represents. We have offered another example of prayer in this chapter. Just because another tradition conceives of a practice differently does not mean that the Christian perspective is wrong. Nor does it imply that the other tradition’s understanding is incorrect.

Yet placing those ideas in dialogue with one another yields impressive insights into the nature of God and how one can approach the Divine. Some may worry that such an appreciation means that we will end up celebrating bad theology, but this criticism rests on the assumption that developing “holy envy” closely mirrors uncritical acceptance of any theology simply because it stems from another tradition. However, it is our experience and argument that Christians actually become more capable interpreters of theological doctrine through interfaith engagement. They are better able to discern theologies within their own and other traditions that render God unintelligible or monstrous.

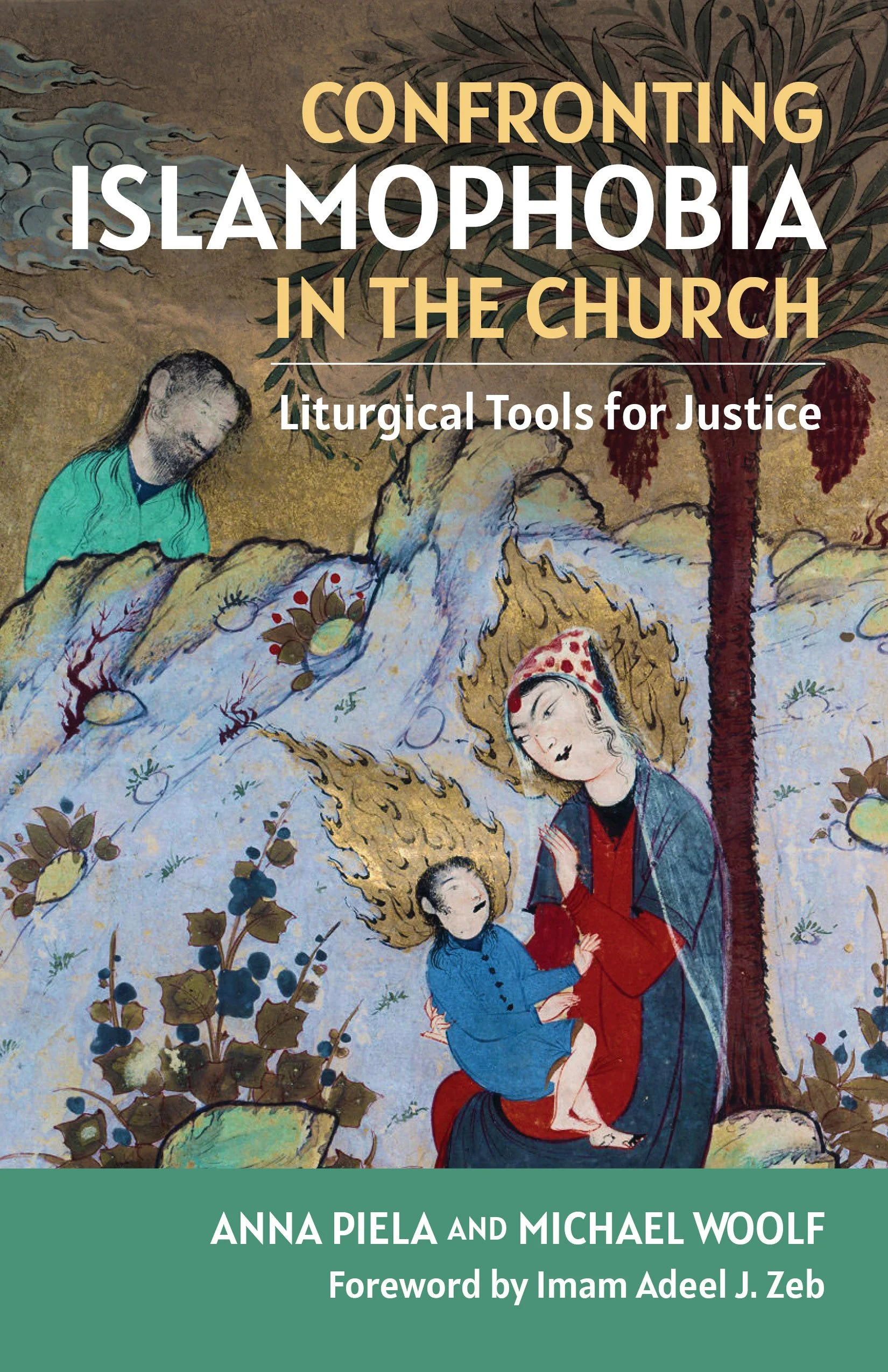

Excerpted from Confronting Islamophobia in the Church: Liturgical Tools for Justice by Anna Piela & Michael Woolf, copyright © 2026 by Judson Press. Used by permission of Judson Press.

Rev. Dr. Anna Piela is senior writer at American Baptist Home Mission Societies and editor of The Christian Citizen. She currently serves as a co-associate regional minister with the American Baptist Churches Metro Chicago. Her most recent book, co-authored with Michael Woolf, Confronting Islamophobia in the Church: Liturgical Tools for Justice (Judson Press 2026) offers a theology of interfaith engagement with Muslims. Piela is also a co-founder of Challenging Islamophobia Together Chicagoland, an initiative that brings together people of all faiths to counter Islamophobia from a religious perspective.

Rev. Dr. Michael Woolf is senior minister, Lake Street Church of Evanston, Illinois. He currently serves as the co-associate regional minister with the American Baptist Churches Metro Chicago. His most recent book, co-authored with Anna Piela, Confronting Islamophobia in the Church: Liturgical Tools for Justice (Judson Press 2026) offers a theology of interfaith engagement with Muslims. Woolf is also a co-founder of Challenging Islamophobia Together Chicagoland, an initiative that brings together people of all faiths to counter Islamophobia from a religious perspective.

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of American Baptist Home Mission Societies.

Get early access to the newest stories from Christian Citizen writers, receive contextual stories which support Christian Citizen content from the world’s top publications and join a community sharing the latest in justice, mercy and faith.